Read My Lips: Just Raise Taxes.

A diatribe against folks who just can’t or won’t recognize that taxes work.

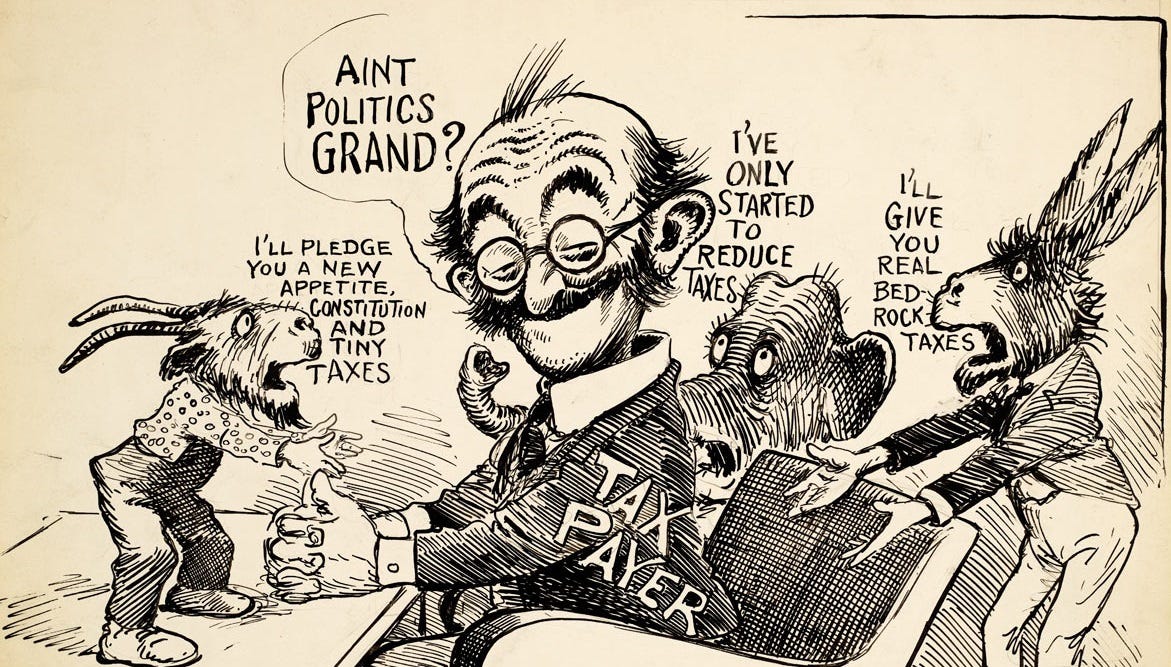

A lot of problems in the U.S. stem from the simple fact that our politicians hate raising taxes. Maybe even as much as they love to take credit for cutting taxes.

The Social Security shortfall? Taxes are too low: The SSA recently estimated that “busting the cap,” or eliminating the taxable maximum, would slash the shortfall by 73 percent.

178,000 deaths annually from excess alcohol use? Taxes are too low: So-called sin taxes on addictive substances have repeatedly proved quite effective.

Too much traffic? You guessed it, taxes are too low: Congestion taxes that fund public transit could keep the streets clear for ambulances and help you commute.

This forosophobia—fear of taxes—leads to a lot of creative “solutions” to the problem that most government programs do in fact need to be paid for. And a lot of bad policy.

One example that’s really stuck in my craw is the recent cut to the grocery sales tax in Alabama. Well, more specifically, the tireless advocacy by the purportedly progressive Alabama Arise1 to cut the grocery tax.

Testifying before the state Grocery Tax Commission in 2023, Alabama Arise policy and advocacy director Akiesha Anderson said the grocery tax “impacts lower income Alabamians more harshly than it impacts higher income Alabamians.”

This, of course, is facially true. As household income goes up, the percentage of it spent on food tends to go down (see the chart below). But nominal household spending, the actual number of dollars and cents spent on food, goes up (again, see the chart below).

So, looking at it one way, Anderson was right. A grocery tax will consume a higher percentage of low-income households’ budgets than it would for high-income households. But looking at it in the way I’d advocate for, high-income families are transferring more dollars and cents into government coffers than poor families are.

In Alabama, the grocery tax was used to top up the Education Trust Fund. While poor families are somewhat more likely to have children under 18, and also more likely to send those children to public schools, the distributional impacts of the program are still a bit hazy.

So let’s imagine that instead of supporting the Education Trust Fund,2 revenue from the grocery tax was evenly distributed among all Alabama families instead. All of a sudden, that horrible “cruel tax on survival” (to quote one Alabama Arise report) would be remarkably progressive.

Using the BLS numbers that ERS chart highlighted again (God bless our federal data wonks), and assuming a 4 percent grocery tax on all expenditures covered by the BLS’ “food at home” category,3 here’s how the grocery tax-and-redistribute system would shake out:

Households in the lowest 20 percent would pay an average of $148.80 in, and get $242.12 back (a net benefit of $93.32)

Households in the highest 20 percent would pay an average of $367.92 in, and get the same $242.12 back (a net loss of $125.80)

The average household in the second and third quintiles would also be a net beneficiary, and the average household in the fourth quintile a net contributor

Maybe the ruby red state legislature in Alabama wouldn’t brook this sort of food communism of course—I’m not actually holding a major grudge against Alabama Arise for engaging in the slow boring of hard boards. But cutting the grocery tax wasn’t a progressive measure just because poor families spend more of their income, as a percentage, on food.

Keeping the “regressive” grocery tax and distributing the proceeds in a wholly egalitarian manner would have been much more progressive than cutting the tax. In fact, the grocery tax was arguably already a net progressive program given the aforementioned distribution of public education needs.

You see, taxes are flows. That old “tax-and-spend” adage is an important reminder of what taxes actually are: ways to fund government programs, whether redistributive or public goods. If a given tax causes a lot of money to “flow” away from poor families, but even more money flows away from rich families and poor families are actually better off afterwards, it’s a progressive program overall.

And it’s almost too obvious to write out but if cutting taxes means leaving the government unable to afford an important program, a tax cut can hurt the purported beneficiaries.4

At the same time that anti-tax sentiment leads to tax cuts meant to help the poor which are actually worse than doing nothing, it also encourages horrific public policy proposals like legalizing gambling.

Keeping Alabama as my frame of reference, politicians there have repeatedly pushed in recent years to license new casinos, open a state lottery, and roll out the red carpet for DraftKings. I, as I’ve made clear before, think that this would be an awful idea.5

But the seemingly ironclad armor for advocates of legalizing gambling in Alabama is, as it has been in dozens of states, “think of the kids.”

Or, in the words of Democratic state representative Barbara Drummond: “I applaud all of those who voted for gaming, but was particularly gratified because of the money that would have been generated for education.”

Basically every politician who supports helping more Alabamians get addicted to gambling says they support it because legalization will help generate tax revenue and fund public schools. Which is, as Hank Green brusquely stated in a recent YouTube video, a “f—ing garbage reason.”

If Alabama politicians actually wanted to fund public schools, they wouldn’t have passed the CHOOSE Act, the state’s shiny new voucher program. Or, better yet, they would just raise taxes.

This 2023 report from the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama more or less makes my case for me: “Since the early 1990s, when PARCA began this analysis of Alabama’s taxes compared to other states, Alabama has had the lowest or second lowest tax collections per capita among U.S. states.”

I won’t deny that at high enough rates taxes can have adverse effects like discouraging investment or reducing growth. But would Alabama going from being the state with the second lowest per capita taxes to “just” the tenth or fifteenth lowest ruin the state economy?

Per that same PARCA report, if Alabama collected as much in taxes per capita as Kentucky does, the state would have $2.2 billion more per year. That’s an awful lot of money that could be given to the state’s public schools, or used to increase state retirees’ pensions.

But because state politicians are so loath to raise taxes, every legislative session civically engaged Alabamians must endure the dog-and-pony show of debates over legalizing gambling.

Now, in blaming politicians for this particular brand of policy malfeasance, I’m not saying that voters secretly love taxes. It’s hardly a secret that most voters like seeing taxes taken out of their paycheck as much as a root canal—with me of course being the rare exception.

But I will say that tax saliency really matters. Lawmakers could (and perhaps should) raise taxes that voters don’t think about when they enter the voting booth. Think value-added taxes, employer payroll taxes, and so on.

I will say that publicizing and promoting what higher taxes help to fund matters. If a taxpayer sees that 4 percent surcharge on their receipt, but also sees all the billboards advertising the new school down the road, maybe their wallet doesn’t ache as much.

These spoonfuls of sugar might not be wholly sufficient to help the proverbial medicine go down, but politicians should at least give it a try. If any elected official is reading this, I, a voter, am begging you: Raise my taxes.

For the voracious readers, here are some articles by other folks that I really liked:

Janet Bufton on liberalism and democracy for Econlib

Jaya Saxena on the paucity of vegan options for Eater

And Bryce Covert on universal pre-K in the Big Apple for New York Magazine

And here are a couple more things I’ve written recently:

An article about Starbucks workers going on strike in Birmingham

And a retrospective of sorts on my work for the Alabama Political Reporter in 2024

For the record, Alabama Arise does do a lot of great work. This peculiar preoccupation of mine shouldn’t distract from that fact.

Which, as a reminder, likely benefits poor families more than well-to-do ones by dint of who actually attends public schools. That is to say, funding public schools properly is ~inherently progressive.

Yes, CES spending figures already include sales and excise taxes. But this is a Substack post, not a journal article. Fair warning, I’m also ignoring administrative costs.

And this is ignoring long-term effects on governments’ fiscal sustainability, bond interest rates, etc.

Because I’m trying to be more concise (kindly note the more), I won’t go into my reasoning here. But read this article in The Atlantic as a starting point.