Municipal Grocery Stores Won’t Have Empty Shelves

Comparisons of Zohran’s proposals to Soviet shortages just show folks don’t care about facts.

If you haven’t been paying attention to the news as of late, this guy named Zohran Mamdani is likely going to be the next mayor of New York City. And he wants to set up a network of city owned and operated grocery stores.

The most infuriating responses to this proposal, in my experience, have been folks talking direct to camera with photos of empty shelves in the Soviet Union behind them. As I’ve pointed out to several people in personal conversations, the issue with Soviet food supply chains, believe it or not, was not retail establishments. And thankfully Zohran is not proposing that municipally run grocery stores should only sell municipally grown crops collected by municipally manufactured harvesters.

However, there have been a couple somewhat more thoughtful critiques. Joe Lancaster, assistant editor of the libertarian magazine Reason, recently penned a piece arguing past publicly run stores have largely been flops. Adam Lehodey put together a similarly critical write-up for City Journal.1

Near the end of Lancaster’s article, he claims that “government-run retail establishments are inherently less efficient than their private-sector counterparts.” He does not provide any evidence. (And no, pointing out that state liquor stores have intentionally higher prices and that a couple city-run grocery stores have closed in the past does not count. Especially when those cities only started running stores after every private company failed to make it pencil out.)

Lancaster also does not acknowledge, besides a mere mention that Zohran said so, that the municipal grocery pilot locations would be on city-owned land, obviating hefty NYC rent payments. Or that a network of municipal grocery stores might be able to benefit from economies of scale and volume discounts. Instead he holds up as a cautionary tale a town-owned store in Baldwin, Fl. that closed last year in large part because the costs of stocking the store were elevated as a direct result of its small size and volume.

Now, unlike state liquor monopolies, commissaries2 do lose money year after year. But they’re also tasked with providing significant savings compared to nearby stores. Frankly, given the quite thin profit margins for grocery stores, it would be a literal miracle if they regularly made a profit.

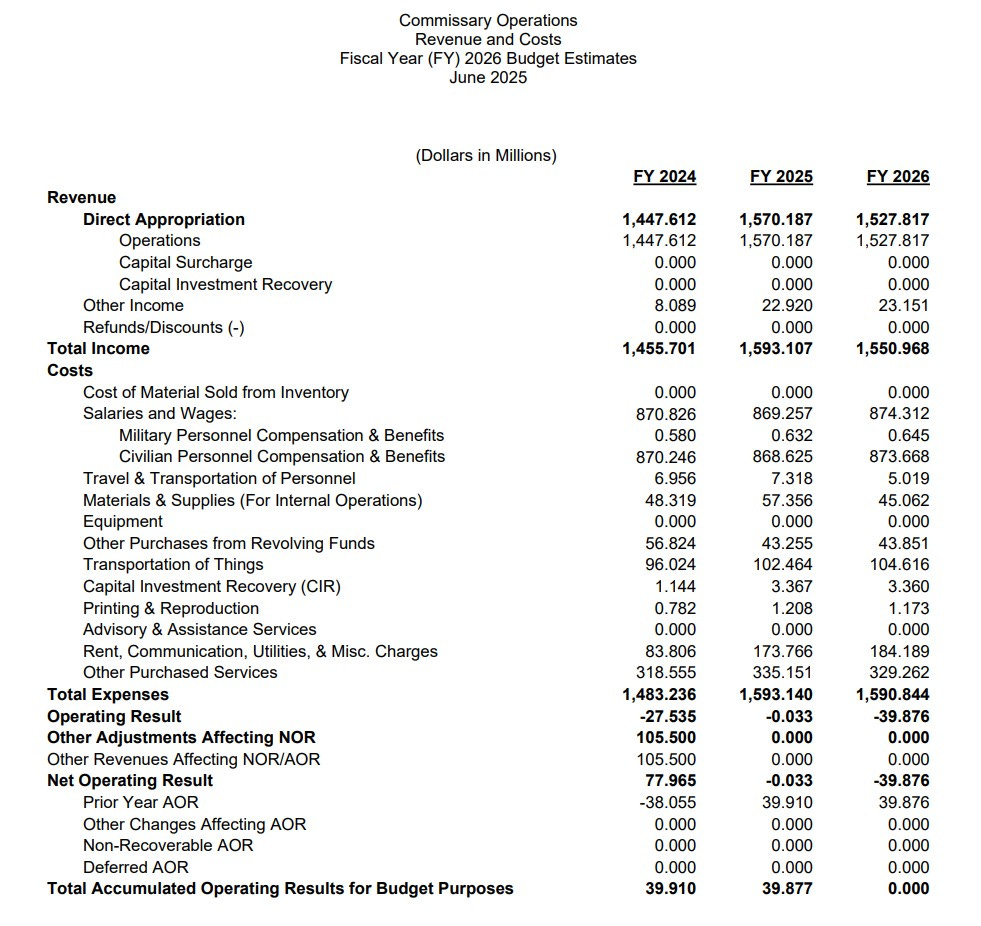

Because they operate at a loss, the Defense Commissary Agency covers operating and capital costs through two major sources: annual appropriations from Congress and a 5 percent surcharge on patron sales. Revenue from actual sales goes into a “Resale Stocks” account where it’s used to restock the stores. Despite this somewhat odd system, relative to one’s mental image of how a private grocery store might work, we still have numbers on how much DeCA sells and spends every year:

So with the over 200 commissaries across the United States raking in a total of $4.7 billion in 2024, operating expenses were around 31.2 percent of net sales. Operating expenses for Walmart, on the other hand, are pretty consistently just above 20 percent of net sales. Perhaps Lancaster was right.

But what looking at operating expenses as a percentage of net sales fails to take into account is that commissaries are supposed to sell their products at 25 percent below civilian market prices. Some quick back of the napkin math shows that if commissaries were selling the same volume but at normal market prices, their net sales would likely be more like $6.27 billion. And their operating expenses as a percentage of these adjusted net sales? Around 23.7 percent.

What with Walmart being rather notorious for how it treats its employees, I personally feel comfortable suggesting that small gap remaining in this one measure of commissaries’ and Walmart’s efficiency can’t immediately be attributed to some “public sector penalty.” I would also hazard that Walmart is likely much faster to shutter underperforming locations than DeCA. If either of those factors was responsible for a small reduction in “efficiency,” my question would simply be why does it matter?

In Lehodey’s piece for City Journal, he writes that one “customer chimed in to say that city-managed groceries would be ‘as well-run as the U.S. Postal Service.’” The USPS delivers “318 million mail pieces daily” for less than a buck an envelope. And despite a mandate to deliver mail to any address in the United States,3 packages and letters delivered by the postal service are overwhelmingly received on time. That’s why the USPS is consistently one of the most well regarded agencies in the federal government according to public opinion polling.

I sure hope that anonymous customer was right. Hopefully we’ll all get to find out.

Here are some articles written by other folks to read:

Jessy Edwards’ interview of Brad Lander for Hell Gate

Sam Adler-Bell’s review of Buckley: The Life and The Revolution that Changed America for The Ideas Letter

As well as Vikas Patel and Preston Mui on macro policy for Employ America

I’ve got some major pieces coming shortly, I hope, but nothing worth sharing just now.

Lehodey gratuitously points out that “opening municipal groceries would not address the underlying forces driving grocery store closures in parts of the city—namely, crime and poverty.” To be frank, if anyone thought otherwise, I’m not sure they understand what a municipal grocery would be.

Grocery stores run by the federal Defense Commissary Agency for the benefit of current and former members of the military.

To quote their unofficial motto, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”